1. Why Do People Struggle with the Axiom of Choice?

The Axiom of Choice (AC) is often framed as an abstract, nonconstructive principle that mathematicians reluctantly accept because it’s “useful but unintuitive.” However, once deeply understood, AC becomes obvious—it becomes something you see before it’s even stated.

Many students struggle with AC because:

- They first encounter it through paradoxes (Banach-Tarski, non-measurable sets) rather than natural applications.

- It’s often presented as a separate axiom rather than a structural necessity in infinite settings.

- The relationship between AC, Zorn’s Lemma, and the Well-Ordering Principle is treated as a formal equivalence rather than a functional equivalence that manifests differently depending on the problem.

For those who haven’t internalized AC, they only recognize it when explicitly told to use it.

For those who have? They see it as soon as they see the problem.

2. How I Instantly Recognize When AC Is Needed

The Axiom of Choice always appears when you need to select an infinite number of independent elements without a clear rule to do so.

Key Structures Where AC is Unavoidable:

✅ Uncountable Products → Any time we need to define something on an infinite Cartesian product, AC is at play.

✅ Measure Extensions → If we’re extending a measure across infinitely many spaces, some form of AC is needed to guarantee existence.

✅ Vector Spaces, Modules, and Algebraic Closure → Many algebraic results, such as the existence of a basis for an infinite-dimensional vector space, are inherently Choice-based.

✅ Functional Analysis & Compactness → Many existence theorems in functional analysis rely on AC at a deep level.

For example, in the Kolmogorov Extension Theorem, we are constructing a probability measure on an infinite product space.

- The moment you see "uncountable product measure," you should already be thinking Axiom of Choice.

- Why? Because you’re defining something across infinitely many spaces without an explicit selection rule.

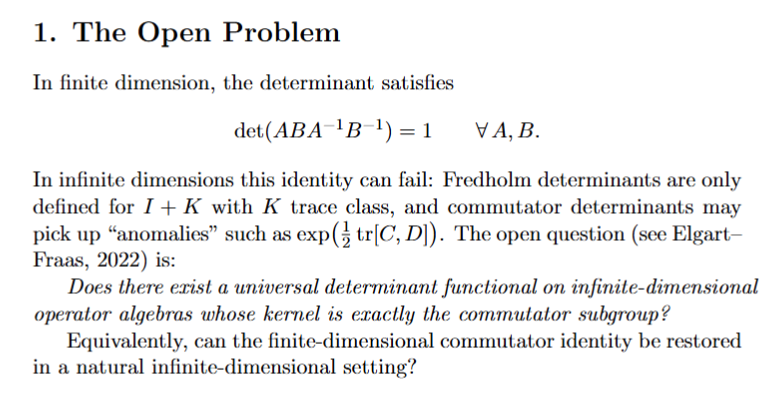

3. The Link Between AC, Zorn’s Lemma, and Well-Ordering

Mathematicians often talk about these three principles as logically equivalent (which they are), but functionally, they are different tools for different perspectives:

| Principle | What It Actually Does | Where It’s Used |

|---|---|---|

| Axiom of Choice (AC) | Selecting infinitely many elements without a rule. | Uncountable products, measure extensions. |

| Zorn’s Lemma | Finding a maximal structure in a partially ordered set. | Algebraic closure, basis selection, maximal ideals. |

| Well-Ordering Principle | Imposing an order on an unstructured set so induction is possible. | Set theory, ordinal analysis, combinatorial proofs. |

Although these are equivalent logically, they feel different in practice:

- If you see infinite choices, think Axiom of Choice.

- If you see maximal structures, think Zorn’s Lemma.

- If you need inductive ordering, think Well-Ordering Principle.

4. Recognizing When to Use Each One

The key is training yourself to predict which one is needed before it’s explicitly invoked.

Example 1: Kolmogorov Extension Theorem → Axiom of Choice

We want to extend finite probability measures to an infinite product space.

- At each finite stage, we have well-defined probability measures.

- But we need to define a consistent measure across all possible infinite sequences.

- This is a selection problem across an uncountable space → AC is required.

Example 2: Sigma-Algebra Generation → Zorn’s Lemma

When defining a sigma-algebra from a product measure, we often take the smallest sigma-algebra satisfying certain conditions.

- The process of constructing a measure-preserving extension across all sets leads to a maximal extension problem.

- This fits into Zorn’s Lemma, since we’re looking for a maximal consistent measure.

Example 3: Banach-Tarski & Well-Ordering

- The Banach-Tarski paradox uses AC, but the deeper issue is the Well-Ordering Principle, which allows us to partition a sphere into pieces that cannot be measured in a standard way.

- The ability to well-order an unstructured set is what enables the paradoxical decomposition.

🔹 AC is about choosing freely across infinite dimensions.

🔹 Zorn’s Lemma is about guaranteeing maximal structures exist.

🔹 Well-Ordering is about imposing structure where none exists.

If you train yourself to see the structure of the problem first, you don’t need to be told which tool to use—you’ll already know.

5. The Algebraic Closure Connection

🚀 Why did I think of Zorn’s Lemma first instead of AC?

Because I was just in an algebraic closure lecture, and that structure was already active in my mind.

- When constructing algebraic closures of fields, we often apply Zorn’s Lemma to get a maximal field extension.

- The process of constructing a measure on an infinite product space has a similar recursive extension structure.

- My brain naturally mapped measure extensions to field extensions, which made me think of Zorn first.

This is why you want to see mathematical structures instead of just theorems—because once you see the deep structure, you start recognizing it everywhere.

Conclusion: The Intuitive Path to AC, Zorn’s Lemma, and Well-Ordering

🚀 If you want to train yourself to think like this, don’t memorize when to use AC—just look for infinite structures.

🚀 If you need infinite selections → AC is unavoidable.

🚀 If you need a maximal structure → Zorn’s Lemma is natural.

🚀 If you need order on an unstructured set → Well-Ordering Principle applies.

Mathematics isn’t just a set of theorems—it’s a set of structures.

Once you see the patterns, the theorems become obvious before they’re even stated.

Discussion